Quick Links:

Slumdog Millennium: We're all Chasing Something

Movies are a way to temporarily forget about life's troubles (or lack thereof) for a while, and enjoy a little excitement or philosophy, or catch a few laughs. When the film stops rolling, what do we take away from the experience? Most movies are entirely forgettable, even those having good entertainment value.  In order to leave a lasting impression, a movie has to tap a deeper vein than the one that holds our basic, everyday thoughts and wants.

In order to leave a lasting impression, a movie has to tap a deeper vein than the one that holds our basic, everyday thoughts and wants.

In this article, I'm going to talk about the chase: the obsessive, almost primal pursuit of one's deepest needs or desires. In this type of story, the protagonist chases a target or ideal as if his or her life depends on it (and sometimes it does). The common thread in all these stories isn't so much the subject matter, but the feeling of what it's like to truly live — to reshape, or abandon altogether, the tedium of life for the sake of living.

I'll be talking about two live-action films in addition to the anime. In my last article, I stated that "anime is diverse in its inspiration because it's a small part of a big world." My goal, of sorts, for this and future articles is to celebrate the ideas that relate the works in various mediums to each other.

The Pursuit of Love and Profit

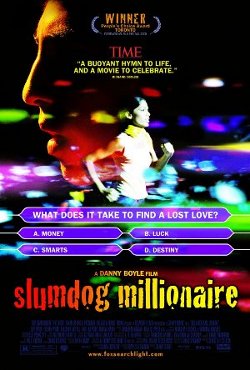

Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire hits close to home for a lot of people. It avoids the cruft and drives at what matters in life — not only for protagonist Jamal, but for all of us. Slumdog starts off as an ordinary tale of injustice, as Jamal is accused of cheating on India's "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" In his defense, Jamal tells the story of his life, and it quickly becomes apparent that the whole thing's about a girl.

The film uses the convenience of a life of poverty, and general lack of things to hold on to, to make Jamal's focus on Latika's welfare seem like the most natural thing in the world. In doing so, it manages to make a compelling case for the rest of us — that if you know what you're after, don't let anything get in the way. But life is a brutal war between competing interests, and finding one to really hold on to is a rare success. Even in the fictional sense, Jamal's drive can't be explained as circumstantial.

The film uses the convenience of a life of poverty, and general lack of things to hold on to, to make Jamal's focus on Latika's welfare seem like the most natural thing in the world. In doing so, it manages to make a compelling case for the rest of us — that if you know what you're after, don't let anything get in the way. But life is a brutal war between competing interests, and finding one to really hold on to is a rare success. Even in the fictional sense, Jamal's drive can't be explained as circumstantial.

In Satoshi Kon's Millennium Actress, a young Chiyoko has a chance encounter with a fugitive political dissident during the chaos of World War II. The man's ambition is to paint the frozen wasteland of a Hokkaido winter, but first he has to escape the police. In the process, Chiyoko meets the man whom she'll burn into her memory as the face of evil — an officer who's after her friend.

The painter then flees to Manchuria (presumably to continue protesting the war), but not before giving Chiyoko a present — a key to "the most important thing there is." Chiyoko then persuades her mother to allow her into the film business as an actress, so that she can follow the crew to China and chase after the most important thing to her.

Chiyoko's chase makes her legendary among film viewers. In role after role, she pursues the man she misses with the whole of her being — cursed to never catch up with him, but still unyielding in her efforts. Repeatedly her "face of evil" destroys any chance at a meeting, while in real life, the loss of her precious memento causes her to settle for another man, only to resume her search later on.

Chiyoko's chase makes her legendary among film viewers. In role after role, she pursues the man she misses with the whole of her being — cursed to never catch up with him, but still unyielding in her efforts. Repeatedly her "face of evil" destroys any chance at a meeting, while in real life, the loss of her precious memento causes her to settle for another man, only to resume her search later on.

Slumdog and Millennium are pretty similar in setup, but each offers a radically different interpretation on the theme. In order for Slumdog to have a resolution, the chase must end. Either Jamal gets the girl or doesn't, but one of those things has to happen, because the entire story is a lead-up to that moment. His race is for the sake of a beginning — a chance at a life together with Latika, and the money he stands to win at "Millionaire" is only a means to an end.

In Millennium, Chiyoko's key immortalizes her desire. In hand it gives her a youthful vitality, and the strength to go after what she wants. Without it she despairs, and succumbs to the tedium of a normal life. For Chiyoko the chase is everything; it's the most important thing there is. While a resolution is possible in this story, it's not necessary.

The Pursuit of Happiness

In the first two movies I talked about, the protagonist's drive is hard to relate to — there's always something inaccessible about figures who inspire. Both Jamal and Chiyoko seem superhuman in their ability to cast aside all else for the sake of what they're after. The next couple of movies depict ordinary people in an all-too-familiar struggle to find their place in the world.

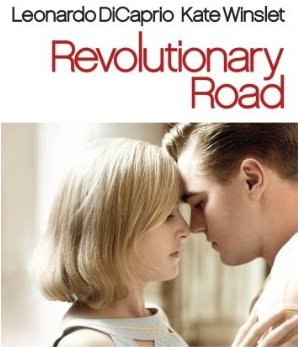

In Revolutionary Road, Sam Mendes's adaptation of the Richard Yates novel, Frank and April Wheeler lead a picture-perfect life in the suburbs, but they aren't happy. Frank hates his job at the Knox company, and April has given up dreams of becoming an actress to become a housewife. April decides to turn the tables, and suggests that they move to Paris, a place that Frank had been to during the war, and admired. Secretarial jobs there pay well, and Frank would be free to figure out what he really wants to do with his life. He wouldn't have to waste his whole existence as a company man. Frank says sure, why not?

In Revolutionary Road, Sam Mendes's adaptation of the Richard Yates novel, Frank and April Wheeler lead a picture-perfect life in the suburbs, but they aren't happy. Frank hates his job at the Knox company, and April has given up dreams of becoming an actress to become a housewife. April decides to turn the tables, and suggests that they move to Paris, a place that Frank had been to during the war, and admired. Secretarial jobs there pay well, and Frank would be free to figure out what he really wants to do with his life. He wouldn't have to waste his whole existence as a company man. Frank says sure, why not?

Perhaps their comfortable, if uneventful existence provides too much inertia, but for a time, the Wheelers act as though they've been given a second chance. It's the City of Lights or bust, and this attitude breathes life into all of their existing relationships. The perplexed looks and perceived envy of coworkers and friends only serve to fuel their desire.

Taking a chance at a new life is a risky thing, though, and it's hard to justify leaving a stable career and uprooting your family for the sake of a feeling. The doubts eat away at Frank in particular, when the Knox upper management hints at a promotion. And April becomes more and more obsessed about the plan, as if her very life depended on this move. Like a slow-motion train wreck, it all starts to unravel.

In another exposé of the crushing weight of complications, Yasutaka Tsutsui's The Girl Who Leapt through Time (adapted into film by Mamoru Hosoda) chronicles the personal development of Makoto Konno, a young girl who discovers that she can jump back in time after a running start. Makoto gets not one, but several chances at a new life, after a near-collision with a moving train reveals her ability.

Makoto's chase is for the perfect outcome. Her first move of course is to correct the chain of events that led to her nearly getting killed, but she doesn't stop there. She discovers instant gratification in the form of time leaps to thwart her sister's pudding-theft plans, or to savor her favorite meal repeatedly. She also leaps to avoid complications like love confessions from friends, preferring for the moment a carefree life.

Makoto's chase is for the perfect outcome. Her first move of course is to correct the chain of events that led to her nearly getting killed, but she doesn't stop there. She discovers instant gratification in the form of time leaps to thwart her sister's pudding-theft plans, or to savor her favorite meal repeatedly. She also leaps to avoid complications like love confessions from friends, preferring for the moment a carefree life.

When Makoto uses a time leap to correct some small mistake or avoid trouble, it often winds up backfiring. Either somebody else gets hurt instead of her, or her situation somehow gets worse, or both. She starts to realize that all her decisions have permanence, even the decision to go back in time. Her efforts to reduce complexity only meets with the opposite effect.

These two are the kind of movies that can really get under your skin. It's almost impossible not to sympathize with Makoto and the Wheelers. There are times when we all feel like victims of the old, bald cheater; things weren't supposed to turn out like this, and something has to be done to fix it. I think the lesson in both movies is to not look to the future as a victim demanding restitution. One's pursuit of happiness must be adaptable to changing realities.

Chasing Life

The idea of going after our desires is akin to survival instinct; it's as natural as the blood flowing through our veins. I think the reason these stories are so compelling, is that they resonate with what makes us human. (A whole host of 1980s rock songs are springing to mind right now. Don't mind me. And no, nothing from Rick Astley is on the list.)

The Bones TV series Wolf's Rain weaves a story where survival and desire are one in the same. It follows a pack of wolves led by a white wolf, Kiba, who run in search of paradise. It is said that only the wolf, the animal, is capable of getting there. Humanity is killing itself off in an all-out war, though there are a few humans left who aren't ready to accept the fate that awaits the rest.

There's a sense in this story that if your desire isn't pure, you won't survive. While the wolves stay focused on the prize, and have the toughness to endure hardship, the humans drop off one by one, succumbing to revenge, grief, and plain physical weakness. Like the Wheelers, they're unable to adapt to the life they seek. On the other hand, the wolves are locked in a battle for what one might call the human soul; the nature of the paradise they'll unearth is on the line. There's a balance to be sought, somewhere in the middle between too vain and too wild.

There's a sense in this story that if your desire isn't pure, you won't survive. While the wolves stay focused on the prize, and have the toughness to endure hardship, the humans drop off one by one, succumbing to revenge, grief, and plain physical weakness. Like the Wheelers, they're unable to adapt to the life they seek. On the other hand, the wolves are locked in a battle for what one might call the human soul; the nature of the paradise they'll unearth is on the line. There's a balance to be sought, somewhere in the middle between too vain and too wild.

April Wheeler couldn't survive as a housewife — that lifestyle was crushing her. Jamal and Chiyoko couldn't stand the idea of a life without their loved ones. Makoto couldn't bear the weight of her mistakes. Regardless of the reasons why, each of these characters both sought something and ran after it. What are you after?